Four hundred and sixty-four years later.

This site constructed under the order of Henry VIII

Outside the Chapel of St. Peter & Vincula:

Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard were also

Executed here – before her.

Five life-size figures, each telling the story

Through gesture, pose, prop,

Female faces turning away.

Four hundred and twenty-five years

after the execution;

One hundred and forty-six years

after the painting.

Me, the only voyeur, the sixth figure. Listening.

“Elizabeth Tilney, Lady-in-Waiting;

Miss Ellen, the Nursemaid;

Sir Thomas Brydges, Lieutenant of the Tower;

The Executioner;

Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England – for nine days.

Quite a gathering of grief, I’d say.

“I was criticised for the lack of historical accuracy

(By Vincent Van Gogh, no less!)

As if history is ever accurate.

Practical realism. Philosophical analysis.

Cruelty and violence – that is my concern

With the past.

Look closely:

“The precocious classical scholar –

Who read Plato for amusement

– with her pallid flesh in her chemise and kirtle.

And note the trembling, vulnerable hands,

Lightly tapping the air, searching for the block

Lashed steady to the floor.

Like all Tudors, she invokes death.

“Look more closely now:

Jump in.

You see the velvet-covered platform

On which she kneels? Reminiscent

Of the beheadings of nobility in

The French Revolution, would you say?

Norman columns, can you see?

“Look, look at the brightness of the blindfold

At the centre of the stage,

How it reflects the red-gold patina of her hair

And forces you to focus on the fear

Beneath, which must shine in her eyes.

“Look at the triptych of warmth:

Tilney’s dress; Brydges’ collar;

The Executioner’s blood-red hose,

Which draws your attention to?

The axe.

Look how smooth the haft, how well-worn the beard,

Yet sharp. ‘I pray you do dispatch me quickly.’

“Let your eyes wander down to the fresh, clean straw.

In moments, the severed head will roll

Towards you, and the blood will seep

Into the straw at your feet.

“And what will you do then?

Will you, too, criticise for historical accuracy?

For the fact that she wears a wedding ring?

Or question whether she be martyr or victim?

“If so, you miss my point:

A deconstructive view will help

You to understand my implicit meaning,

Where pluralism, in my art, is political.

History repeats itself.

Cruelty and violence – that is my concern

With the past.”

I first viewed this painting at the National Gallery in 1979. It had been bequeathed to the Tate at the start of the 20th century, but by 1928 had been consigned to storage (being deemed as far too ‘chocolate-boxy’ and twee by highly-regarded art historians) and did not emerge again until 1974. And I was simply astounded by the power this painting exudes.

Quick bit of history here: the young King Edward VI, knowing he was dying, named both Mary and Elizabeth as illegitimate in his will. After his death, his first cousin once removed and a Protestant – Lady Jane Grey – was proclaimed Queen. Mary Tudor – a staunch Catholic – then claimed the throne, which Jane was forced into relinquishing only nine days into her reign. Jane, her husband Lord Guildford Dudley and her father (Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk) were imprisoned in the Tower of London, accused of high treason. Mary Tudor sent her chaplain, John Feckenham, to Jane in prison, to try to persuade her to convert to Catholicism: Jane chose to die rather than recant her faith. On 12th February 1554, Jane – aged just sixteen – and her husband were beheaded. Her father met the same fate two days later.

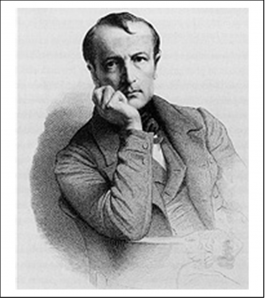

Why might Paul Delaroche have chosen this execution, four hundred and twenty-five years after it took place, for the subject of his painting? A clue probably lies in the period of French history between 1814 (the restoration of the monarchy) and the revolution of 1848. In 1831, Delaroche had produced a painting of Cromwell gazing down on the corpse of King Charles I in his coffin. No doubt Delaroche was wise not to have taken his own country’s contemporary unrest and trauma as the subject of his art. But in taking the deaths of monarchs from English political history as his subjects, perhaps he was fulfilling both the Anglophilia of the conservative French art world and making a timely comment on the de-glorification of the ruling classes.

On 12th February 2018, I was back as a tourist at the Tower, only coincidentally then remembering that it was four hundred and sixty-four years to the day since this grotesque act of political violence.

Angela Valentino, Teacher of English