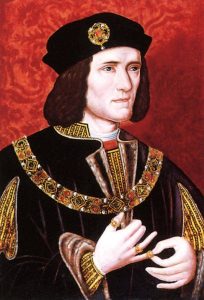

Richard III is one of Shakespeare’s most notable plays, infamous for the protagonist: King Richard III. Laurence Olivier famously played Richard in a 1955 film adaption. Olivier characterised all future portrayals: the mad-eyed stare; the cowardliness; raspy voice; and most infamously, the crooked shoulder and withered arm. This deformity is an enduring theatrical image despite it being little more than a caricature to mesmerize and excite an audience. It was not until September 2012, when Richard III’s remains were uncovered under a car park in Leicester, that Shakespeare’s ‘character’ was called into question when Richard’s skeleton was examined. There was an obvious curvature in Richard’s spine, and according to a document from 1513 by Thomas More, he was: “little of stature, ill featured of limbs, crook-backed, his left shoulder much higher than his right, hard-favoured of visage.” Richard III died in 1485, and 1513 was during Henry Tudor VIII’s reign; this report could have been biased towards the Tudors. 1

Richard III is one of Shakespeare’s most notable plays, infamous for the protagonist: King Richard III. Laurence Olivier famously played Richard in a 1955 film adaption. Olivier characterised all future portrayals: the mad-eyed stare; the cowardliness; raspy voice; and most infamously, the crooked shoulder and withered arm. This deformity is an enduring theatrical image despite it being little more than a caricature to mesmerize and excite an audience. It was not until September 2012, when Richard III’s remains were uncovered under a car park in Leicester, that Shakespeare’s ‘character’ was called into question when Richard’s skeleton was examined. There was an obvious curvature in Richard’s spine, and according to a document from 1513 by Thomas More, he was: “little of stature, ill featured of limbs, crook-backed, his left shoulder much higher than his right, hard-favoured of visage.” Richard III died in 1485, and 1513 was during Henry Tudor VIII’s reign; this report could have been biased towards the Tudors. 1

Emyr Wyn Jones suggests in his 1980 medical postscript, studying Richard III’s disfigurement, that More’s analysis affected Shakespeare’s depiction of the king. Furthermore, Jones also proposes that Richard’s deformity may have been Sprengel deformity, a possibly hereditary condition.2

Sprengel deformity, as Medscape puts it, is: “a complex anomaly that is associated with malposition and dysplasia of the scapula” 3 (Mihir M Thacker. 2016). This is close to what Jones and More describe. These medical records do not prove that Shakespeare’s physical depiction of Richard III was entirely fictional, because these sources were written after his death. However, Richard’s body was uncovered 32 years after Jones’ medical report, so Jones could have only relied on medical reports written during Tudor times. Furthermore, Shakespeare implies in Act 1, scene 1, that the reason for Richard’s malevolence comes down to his physical appearance by saying: “And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover to entertain these fair well-spoken days, I am determined to be a villain and hate the idle pleasures of these days”. When Richard was uncovered in September 2012, his spine did indeed have an s-shape.

The Telegraph, in response to the archeological discovery (which was supported by Channel 4), stated that this spinal deformity would not have weakened him and he was a “formidable warrior” (Claire Duffin, 2014). The Telegraph also states that a teacher, Dominic Smee, helped experts assess Richard’s spinal condition as Smee himself had a similar s-shape curvature in his spine. A specialized suit of armour was made for him, and he partook in a cavalry charge. The armour “provided support, strengthening his upper body” (Claire Duffin, 2014). Smee said: “With my scoliosis, you might think I was a bit stooped but you wouldn’t really see there was a problem unless I was undressed. With Richard III, it’s looking like the same story. Far from being a hunchback, he’d have looked pretty normal in a suit of armour. He’d just have had to have armour specially made.” 4. This directly contradicts Shakespeare’s Richard because, as shown by Olivier, he had a defined stoop and limp that characterised him to great effect.

An article by Emma Mason of History Extra adds on to this by stating that the reason for Shakespeare depicting Richard III in such horrible manner was due to the historical backdrop of Elizabeth I’s death, which worried the influential Cecil family who did not want a Catholic on the English throne. Mason states that it is believed today that Shakespeare was Catholic, and that Richard III may have been based on a “more contemporary player” (Mason, E. 2016). To prove how inaccurate Shakespeare was, Mason writes that Richard could not have killed the Duke of Somerset at St. Albans in 1455 because Richard would have been “two-and-a-half years old”. Adding onto this disassembly she states: “Shakespeare’s Richard delights in arranging the murder of his brother Clarence by their other brother Edward IV through trickery when in fact Edward’s execution of Clarence was believed by contemporaries to have driven a wedge between them that kept Richard away from Edward’s court.” Elizabeth could be the “sun of York” (Act 1 scene 1, Richard III) because she is “made summer by her lack of an heir that allows winter, his real villain, in during the autumn of her reign.” 5. Mason also adds that this line bridges the play’s timeline to Shakespeare’s contemporary. William Cecil’s (Elizabeth I’s advisor) son was Robert Cecil, and he was described by Motley in 1588, in History of the Netherlands, as “A slight, crooked, hump-backed young gentleman, dwarfish in stature” and according to Mason follows this up with “massive dissimulation – that would constitute a portion of his own character.” 6. This directly ties into the line in Act 1 scene 1 of Richard III: “And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover to entertain these fair well-spoken days, I am determined to be a villain and hate the idle pleasures of these days.” 7. Therefore, according to Mason, the reason for Shakespeare’s negative depiction of Richard III was because he was written to be a direct representation of the Cecil family. This is made effective by using the late King Richard because he was Elizabeth’s grandfather’s enemy, symbolising that the Cecils were Elizabeth I’s enemy as well as England’s.

Now that Shakespeare’s depiction of Richard III can be doubted, so can his personality: cowardice is one of Shakespeare’s Richard III’s main attributes. The line “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!” 7 from Act 5 Scene 4, is spoken by Richard III after he is de-horsed during the battle of Bosworth Field. Richard is declaring aloud that he will trade a horse for his throne so that he may flee the battle in an act of cowardice, retaining his life at the cost of losing his kingdom to Henry Tudor. Historically, Richard had fought in many battles, his first in 1471 at Barnet against Henry VI during the Wars of the Roses. Richard would have been 19 years old, making him a seasoned veteran at the time of Bosworth in 1485. To further debunk his cowardice shown in the play, Richard III led his army’s cavalry against Tudor forces at Bosworth. That is not the act of a coward. Furthermore, a post-mortem conducted on Richard’s body lead by Leicester University, said the following: “None of the skull injuries would have been possible to inflict on someone wearing a helmet of the type favoured in the late 15th century.” Richard III received 10 injuries at Bosworth, possibly more according to the report. The post- mortem says in conclusion: “all of the injuries happened at around the time of death.” 8.

In addition to Leicester University’s analysis, the US National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health conclude the discovery: “The wounds to the skull suggest that Richard was not wearing a helmet, although the absence of defensive wounds on his arms and hands suggests he was still otherwise armoured.” 9. Judging by the wounds, Richard was involved in serious combat and suffered from it, plus having his body mutilated after death. Following the evidence, we can debunk Shakespeare’s portrayal of Richard III as a scheming coward as unreasonable.

Richard III depicts the closing years of the Wars of the Roses, which lasted from 1455 to 1485 at Bosworth Field. It was certainly horrific: the high death toll of the Battle of Towton as well as the war’s overall length does suggest that the Wars of the Roses were not a trifle. Humanity, in general, has only recently understood the horror of war, having learned that lesson in the First World War, and it is a cliché to say that war was once seen as noble before 1914.

One line from Richard III that suggests that Shakespeare disapproved of this war: (Act 2, scene 4) “Make war upon themselves, brother to brother, blood to blood, self against self. O preposterous and frantic outrage.” This indicates that the Wars of the Roses turned even the closest of relations against one another in a “preposterous and frantic outrage”, again indicating that this war was not truly necessary, although savage. Richard’s opening monologue of Act 1, scene 1, describes the aftermath of the first half of the Wars on the Roses: “Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths; our bruised arms hung up for monuments; our stern alarums changed to merry meetings, our dreadful marches to delightful measures. Grim-visaged war hath smooth’d his wrinkled front;” From this line, it can be deduced that the Wars of the Roses were long and gruelling, as described from “dreadful marches” as well as the transition from war to peace within the passage. This is continued in Henry VII’s monologue in Act 5, scene 8: “England hath long been mad, and scarr’d herself; the brother blindly shed the brother’s blood, the father rashly slaughter’d his own son, the son, compell’d, been butcher to the sire: all this divided York and Lancaster, divided in their dire division.” 7. This alludes to the Duchess of York’s lament over the war, on how brothers kill brothers (a fact commonly shared between these two lines) and how families have been turned against one another all because of war. All of this is evidence for war being depicted negatively in Richard III, which was the opposite of my expectations. I believed that due to censorship and the historical context, Shakespeare might have celebrated the winning side of the war. However, King Richard can be said to be depicted unfairly as villainous; he is deformed, only fit for times of war, not peace. He conspires to be King, murders his brothers, and conspires against Edward’s sons after tricking them into imprisonment in the Tower of London.

Meanwhile the Earl of Richmond, Henry Tudor (Queen Elizabeth I’s ancestor), is depicted in the utmost positivity. Richard III even mentions that Henry VI “did prophecy that Richmond should be King” in Act 4 scene 2. Richmond in Act 5, scene 3 speaks to his comrades-in-arms against Richard’s “tyranny” and exclaims that he vows to vanquish Richard through “God’s name cheerly on, courageous friends, to reap the harvest of perpetual peace by this one bloody trial of perpetual war.” 7. According to this line, Henry Tudor seems too good to be true: he fights in God’s name against tyranny to claim peace by way of war. Thus, this positive depiction of Henry was likely to please Queen Elizabeth and to give the audience a hero to root for.

Whoever murdered the Princes in the Tower remains a mystery figure. Some believe that Henry VII killed the princes, as they could have been seen as the rightful heirs to the throne. But Shakespeare was writing in the Tudor Dynasty, so vilifying one of their ancestors would have been sacrilegious.

Paul Gallagher in the Independent, in August 2015, shed some light on “perhaps the greatest of all cold cases”. He writes that it was widely assumed Richard III killed the Princes in the Tower in the summer of 1483, soon after King Edward’s death. Gallagher spoke to Philippa Langley, one of the leading archaeologists in the discovery Richard’s tomb, and she said: “I have three lines of investigation – two that have never been investigated before.” She goes on to say that “we do know that Henry Tudor tried to destroy all copies of Richard’s legal right to the throne, the Titulus Regius. What we don’t know is how much of the other paperwork he destroyed quietly behind the scenes.” Ms. Langley is trying to find any surviving documents about the Princes in the Tower in Europe, as Henry Tudor destroyed the rest. Ms. Langley added that she will work with professional cold case investigators and “they all say the same thing: that’s it’s very questionable whether there was a murder at all, considering what happened with all the pretenders that arrived under Henry Tudor’s reign; and second, that Richard III is not their prime suspect – because they go on motive, opportunity and proclivity.” 10. This sheds some light onto another potential conclusion: that the Princes in the Tower were merely another set of pretenders to the throne, and could have been killed by either Richard or Henry as both men had no legal right to the throne.

Dr. John Ashdown Hill claims that Richard III was rightful Lord Protector until Elizabeth Woodville (King Edward’s wife) attempted to illegally remove Richard. Lord Rivers was executed because he supported this coup. The article continues to legitimise Richard’s claim by stating: “The bishop told the Three Estates that Edward IV’s marriage to the mother of the ‘princes’ had been bigamous, because he (the bishop) had himself married Edward to Lord Shrewsbury’s daughter, Eleanor Talbot, a devout lady of royal descent. Since this marriage had preceded the secret Woodville wedding – at which time Eleanor had still been alive – the Three Estates decreed that Edward IV had never legally been married to Elizabeth Woodville (so she was not his widow), and that the couple’s children were illegitimate, and could not inherit the crown”. If this is true, then Richard III was legally King. Henry VII would be illegitimate. Thus, after the Three Estates found out: “Richard was then offered the crown of England by the Three Estates of the Realm.” 11.

It is difficult to side with either Richard or Henry; we can never know for sure who killed the Princes in the Tower because we have not discovered the suitable documents yet. Shakespeare’s Richard III makes it doubly difficult because we are inclined to believe the story told in it, despite the evidence that it might have been censored to suit a Tudor perspective. There is no doubt that poetic licence was used to captivate the audience’s interest in a character, because by comparing the evidence behind the real Richard Plantagenet, and Shakespeare’s Richard, the nefarious yet loveable villain, we get two very different people.

Max Kirkillo-Stacewicz, U6th IB pupil

1. More, Thomas. As Quoted by Aird and McIntosh not 8. (1513-1566) “The History of King Richard the Thirde”. Referenced too in Jones, Emyr Wyn in “Richard III’s Disfigurement: A Medical Postscript” in a medical study. Retrieved online from JSTOR in “Richard III’s Disfigurement: A Medical Postscript.” www.jstor.org/stable/1260393

2. Jones, Emyr Wyn. “Richard III’s Disfigurement: A Medical Postscript.” Folklore, vol. 91, no. 2, 1980, pp. 211–227. Retrieved online from JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/1260393

3. Mihir M Thacker, MBBS, MS(Orth), DNB(Orth), FCPS(Orth), D’Ortho. David S Feldman, MD. “Sprengel Deformity” (Updated 2016). Retrieved online from Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1242896-overview

4. Claire Duffin. Article, published by the Telegraph. (2014). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/11038600/Richard-III-the-hunchback-king-really-could-have-been-a-formidable-warrior-…-and-his-body-double-can-prove-it.html

5. Emma Mason. Article, published by History Extra. (2016) Retrieved from HistoryExtra online. http://www.historyextra.com/article/culture/have-we-completely-misinterpreted-shakespeares-richard-iii

6. Motley. (1588). “History of the Netherlands.” Retrieved from Mason, E’s article from History Extra. http://www.historyextra.com/article/culture/have-we-completely-misinterpreted-shakespeares-richard-iii

7. Shakespeare, W. & Spencer, T.J.B & Wells, S. & Edmondson, P. Published by Penguin Shakespeare (2005) “Richard III”. Script of Richard III for the National Youth Theatre. (Original script written in 1592 by Shakespeare, W).

8. University of Leicester. (2013) “Richard III – Science – Analysing the Skeleton.” Retrieved from the University of Leicester online. http://www.le.ac.uk/richardiii/science/whattheonesdontsay.html

9. Lancet. (2015). “Perimortem trauma in King Richard III: a skeletal analysis.” Retrieved from PubMed.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25238931

10. Paul Gallagher. Article, published by the Independent. (2015). “The Princes in the Tower: will the ultimate cold case finally be solved after more than 500 years?” http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/the-princes-in-the-tower-will-the-ultimate-cold-case-finally-be-solved-after-more-than-500-years-10466190.html

11. Dr. John Ashdown Hill. Article, published by Catholic Herald. (2015). “In Defence of Richard III”. http://www.catholicherald.co.uk/commentandblogs/2015/03/11/in-defence-of-richard-iii/